UMass Lowell Professor Emeritus Michael Jones champions the Olympics

Former legal studies program director serving as appeals judge for summer games

Since he first dipped a toe in the water of Olympic competition in 1972, UML Professor Emeritus Michael E. Jones has remained involved with the games.

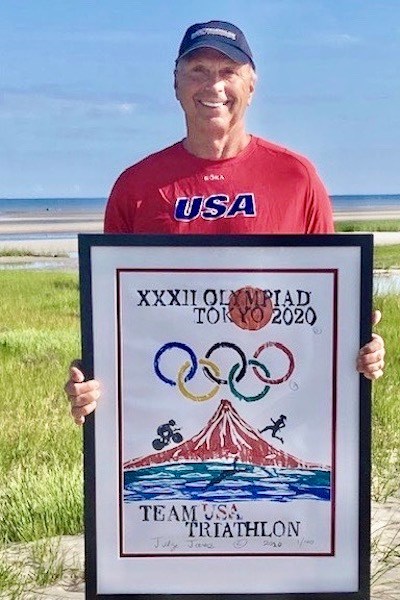

Jones, who tried out unsuccessfully for the U.S. Olympic swim team in 1972, went on to build a career as a lawyer, judge, educator and artist. He has been commissioned to paint several official Olympic posters for the triathlon (Tokyo is his sixth), as well as Michael Phelps’ official Olympic portrait. He also has served in legal capacities for Olympic teams — and is currently working remotely as an appeals judge for the 2021 Summer Olympics.

Former director of UML’s Legal Studies program, Jones continues to teach as an adjunct instructor. He has remained an elite-level swimmer, runner and triathlete, and now trains regularly with his wife, Christine.

We caught up with Jones to get his perspective on this year’s Olympics.

Q: You had your own brush with Olympic competition, trying out for the 1972 U.S. swim team alongside Mark Spitz. You have remained actively involved with the Olympics ever since. What do the Olympic Games signify to you?

A: Asking about the meaning of the Olympics reminds me of a recent headline in The New York Times. It read something to the effect that in the midst of a pandemic, human rights challenges, an overburdened country that does not want the games, billions spent on stagecraft, no spectators, rampant cheating, and concerns about the environment, free speech and gender roles, isn’t it time to cancel them?

Despite these legitimate concerns, the games still are a wonder to watch. It’s a treat to witness athletes testing themselves against the best of the best. For athletes, coaches and sports administrators, competing at the Olympics represents the pinnacle performance opportunity after a lifetime of training and hard work. These are moments I continue to admire and respect.

Q: How did you end up doing work for the Olympic teams?

A: In the 1980s, I served as regional counsel for USA Swimming. At the Olympic trials in 1988, the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) decided to officially test athletes for performance-enhancing drugs. Angel Martino won the 50- and 100-meter freestyle events at the trials, and then tested positive for an illegal steroid. Nothing like this had ever happened before in U.S. swimming. There were no rules in place to decide what to do next other than to ban her. I was part of the legal team that decided on fairness grounds to move all the other competitors up one spot instead of calling the swimmers back to the pool and conducting a re-swim.

This experience was helpful as I became more involved at USA Triathlon (USAT), the official Olympic governing body for that sport. Until last December, I served as a member of the board of directors for USAT.

Behind the scenes, I assisted in advising the USOPC, and indirectly members of Congress, on how to prevent a reoccurrence of the abuse Dr. (Larry) Nassar perpetrated on young female gymnasts, including Simone Biles, for decades. From this dialogue, Congress mandated the creation of the U.S. Center for Safe Sport, which is charged with safeguarding athletes from bullying, harassment, hazing, physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse and sexual misconduct.

Q: We hear you are currently working for the Olympics as an appeals judge. What’s involved in that?

A: Earlier this year, I was named to the eight-person World Triathlon Tribunal. It is a select group of lawyers and judges from around the world whose task is to adjudicate legal and ethical multisport-related disputes. From this group of eight, three persons were selected to sit as appeals judges to resolve protests not involving performance-enhancing drugs at the Tokyo Olympic Games in the sport of triathlon. I am one of the three members who was asked to sit as appeals judge.

In light of COVID-19, the Japanese government imposed stringent travel and movement restrictions for those attending the games, even in an official capacity. As a group, we decided not to attend in person. Instead, the panel has the benefit of sophisticated visual and audio technology at our disposal to hear and see witness testimony.

Q: What are your favorite Olympic moments, and why?

A: In Tokyo, freestyle swimmer Caeleb Dressel finally won Olympic gold in an individual event. Caeleb’s sprint coach at the University of Florida (Steve Jungbluth) is a guy I coached as a young swimmer at the Lowell YMCA. We’ve stayed in touch. Connections like this give one a special sense and meaning of the value of teaching, and how one life can positively affect the lives of others.

Watching Michael Phelps win eight gold medals at the 2008 Beijing Games and break Mark Spitz’s record in 1972 of winning seven gold is a favorite moment because of my personal connection to both swimmers.

Jenny Thompson is a New England native who competed in four Olympics, winning 12 medals, including eight gold. I remember her when she was swimming as a youngster at pools in Lowell, Cambridge and Manchester, New Hampshire. After her swimming career was over, I got to know her as an adult and I nominated her to be honored by Boston’s Sports Museum for inclusion on its honor roll of sports legends.

Q: Mental health is a huge subject in sports right now. Simone Biles exited an Olympic event citing a mental health issue, Naomi Osaka withdrew from the French Open to address her mental health and Michael Phelps is among those who have been vocal about the value of therapy and self-care. What is going on, and how might increased self-awareness and care change the landscape of sports and competition?

A: A complex societal issue has jumped to the top of the Olympic conversation because of Simone Biles’ decision to listen to her head and body and publicly say, “It’s OK not to feel OK.” And there’s also Michael Phelps’ courageous voice on the subject. When athletes are physically injured, we visually see their injury and feel their pain. When their injuries are invisible, we lose our reference points, and all too often criticize poor performances without understanding their mental health condition.

The daunting relationship between performing at an elite level in one of the foremost sports competitions and matching society’s social media expectations for Olympic athletes is unparalleled.

Athletes like Phelps, Biles and (former semi-pro volleyball player and mental health advocate) Victoria Garrick are now telling their stories and inspiring others to seek professional help.

The pressure to perform extends beyond the playing field to the classroom. Increasingly, whether teaching online or face-to-face, more and more of my students are experiencing significant symptoms of anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions. Encouraging them to seek professional help by taking advantage of the university’s resources has become an important component of our teaching responsibilities.