NSF awards researchers $1.5M to study rotifers

Tiny aquatic animals play vital roles in ecological systems

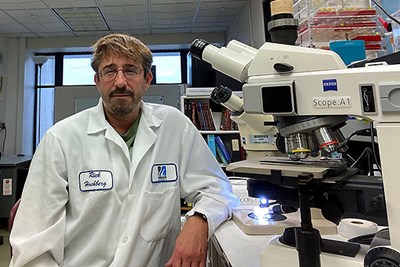

The National Science Foundation (NSF) has awarded a team of researchers from UMass Lowell, the University of Texas at El Paso and Ripon College in Wisconsin a four-year grant worth more than $1.5 million to understand the biology and life cycle evolution of rotifers, microscopic invertebrate animals that are a key link in the aquatic food chain.

“Rotifers can be found anywhere there is liquid water,” says UML Biology Assoc. Prof. Rick Hochberg, the project’s principal investigator. “They inhabit shallow seas, lakes, ponds, streams, irrigation ditches, ephemeral basins in deserts, meltwater puddles on glaciers and thin layers of water on soils and plants.”

According to Hochberg, rotifers play vital roles in ecological systems as both predator and prey, and the nutrients they contain are passed up the food chain to insects and fish.

However, even though they are ubiquitous, not much is known about the changes over time in the life cycles of these creatures, which range in size from 50 microns to 2 millimeters.

“Despite more than two centuries of study, there are still substantial gaps in our knowledge of the rotifers’ reproductive development and evolution,” Hochberg notes.

To address this issue, the team will use genetic analyses and comparisons of anatomy based on advanced microscopic imaging to determine the evolutionary history of a class of rotifers called Monogononta, which comprises the largest group with more than 1,500 described species. The researchers will examine how their life cycles and reproductive modes changed as the group evolved.

“We will use molecular sequencing techniques to build an evolutionary tree, so we can map the changes in reproduction and anatomy that have occurred over the course of about 500 million years of rotifer evolution,” says Hochberg.

“Our study will result in the description of new species, provide data on the importance of rotifer life cycles in freshwater ecosystems, and provide new insights into the evolution of one of the largest groups of freshwater invertebrates.”

UMass Lowell’s portion of the NSF grant, totaling $783,000, will support the research and training of undergraduate and graduate students as well as a postdoctoral scientist.

“As part of the project, we will produce museum displays and contribute to online databases,” says Hochberg. “We will also hold a symposium on invertebrate reproduction at a national meeting, as well as two educational workshops aimed at acquainting students and scientists with the merits of studying rotifers.”

A Complex Life Cycle

The name “rotifer,” which means “wheel-bearer” in Latin, refers to the crown of cilia – short, hairlike structures – around the mouth of the organism that rotates like a wheel.

According to Hochberg, rotifers are most well-known for their complex jaws, which they use to feed on bacteria, algae and other tiny animals, as well as their high rate of reproduction in freshwater lakes and ponds.

He says their ability to attain population densities of greater than 1,000 animals per liter of water is a result of their unique form of life cycle, called “cyclical parthenogenesis,” in which female rotifers produce eggs in the absence of sex.

“Here, the unfertilized eggs are clones of the mother and they hatch rapidly to increase the population size,” Hochberg explains. “As a result, when examining rotifers from a lake or pond, nearly all individuals are females throughout the year.”

However, for a brief period, often in the fall, some females will become sexual and produce two types of eggs: female eggs and male eggs.

Males, which are generally non-feeding, short-lived (a few days) and dwarves (half the size of the females), will seek out sexual females for reproduction, Hochberg says.

“Sex between these two individuals produces a third type of egg, called a resting or overwinter egg,” he explains.

These eggs have unique shell layers that allow them to withstand harsh environmental conditions, such as snow, ice, rain and heat. They will generally hatch the following spring.

“They are also genetically unique from their mothers because they are the result of sexual recombination, not asexual cloning,” he says.