Good COP, Bad COP: UML delegates reflect on U.N. Climate Summit

Interdisciplinary team of faculty members view COP26 through varied lenses

Was COP26 worth it?

That’s the question on the minds of seven UMass Lowell faculty members after returning from the recent United Nations global climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, a two-week conference of nearly 200 countries that resulted in several substantial international agreements — but that climate activists such as Sweden’s Greta Thunberg say was just a lot of “blah, blah, blah.”

“Whether it was worth it depends on what we do next,” says Assoc. Teaching Prof. of Sociology Thomas Piñeros Shields, who was part of the interdisciplinary delegation representing UML’s Climate Change Initiative (CCI) in Glasgow. “It depends on whether we choose to feel cynical and just walk away, or if we say now’s the time to step up and do more.”

UML was granted “provisional observer status” for this year’s COP, or Conference of the Parties, where more than a quarter of the roughly 40,000 participants were observers from non-governmental organizations. In Glasgow, UML was approved for full observer status for future summits — starting with COP27 next year in Egypt.

Piñeros Shields attended the first week of COP26 along with Assoc. Prof. of Education Jill Lohmeier, Asst. Prof. of Chemistry Juan Artes Vivancos and CCI Program Associate Carolyn McCarthy.

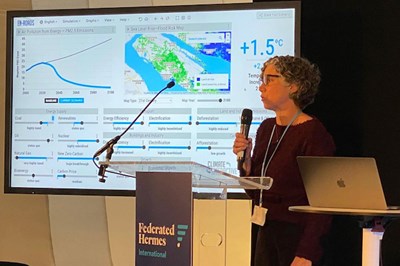

During the second week, UML was represented by Assoc. Prof. of Political Science and International Relations Jarrod Hayes, Assoc. Prof. of Plastics Engineering Meg Sobkowicz-Kline, Research Prof. of Economics Dave Turcotte and Prof. of Environmental, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Juliette Rooney-Varga, who is director of the CCI and co-director of UML’s Rist Institute for Sustainability and Energy.

Language Barriers

This was the second COP for Rooney-Varga, who attended the 2015 summit in France that led to the Paris Agreement, which set a goal of limiting the rise in global temperatures to just 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, above pre-industrial levels. The world has already warmed 1.1 C.

“Even though we’re running out of time, we are seeing real progress,” says Rooney-Varga, who pointed to several hopeful developments in Glasgow, including pledges by more than 100 countries to cut methane emissions by more than 30% by 2030 and to end deforestation in 85% of the world’s forests by decade’s end.

While attendees were disappointed to see the Glasgow Climate Pact language watered down at the last minute — with the “phasing out” of coal and fossil fuel subsidies changed to “phasing down” at the behest of India — Rooney-Varga says the fact that coal and fossil fuels were even included was a victory.

“They weren’t mentioned in the Paris Agreement, so it’s a big deal,” she says.

It was also the second COP for Hayes, who attended the 2019 summit in Madrid (it was not held last year because of the COVID-19 pandemic). As a scholar of international relations, Hayes says he was interested in how the United States positions itself on the global stage regarding climate change — particularly in light of its strategic rivalry with China.

“China was weak at this COP,” says Hayes, who notes that, unlike President Joe Biden, Chinese President Xi Jinping did not attend the summit. “China has not bought into a lot of the targets that other countries are pushing for, such as pledging to peak emissions by 2030 or reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.”

But Hayes says the United States didn’t go far enough when it comes to ending subsidies for coal and fossil fuels. John Kerry, the U.S. special envoy for climate change, insisted on language for phasing out “unabated” coal (coal that doesn’t include carbon-capturing storage) and “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies — which are seen by some critics as potential loopholes.

“Even though there was a huge opportunity for the U.S. to take a leadership position and address this problem, it was not willing to walk through the door that China has opened for it,” says Hayes, who ascribes that to “the domestic politics of the U.S. and the contentiousness of climate change, a clash that is not experienced in a lot of other countries around the world.”

All-inclusive Solutions

For Lohmeier, who researches how art can be used to engage people in climate science education, attending COP26 was an “extremely worthwhile” opportunity to learn about education practices around the world.

She was struck by the fact that 23 countries pledged to include climate education in their national curricula while also committing to net-zero schools.

“The fact that they could get an entire country to say, ‘We think this is important,’ is different than how we treat climate education in the U.S.,” she says.

Sobkowicz-Kline, meanwhile, says COP26 was “the most inclusive and diverse conference” that she’s ever attended.

“One of the reasons I attended was to understand how to get people from so many different walks of life — with different languages and disciplines — to all row in the same direction,” she says. “Gatherings like this are essential for opening up that conversation and solving complex problems.”

Piñeros Shields says he approached COP26 as an ethnography — a way to “really think about the youth activism” taking place on the streets outside the conference, led by the likes of Thunberg.

“The first question I got from my students is, ‘Have you met Greta yet?’” says Piñeros Shields, who didn’t meet the teenage activist in person — but who could clearly sense the protesters’ presence at the summit.

“Outside social movements are making increasingly strident moral appeals and demands on the older generations to do something,” he says. “We’re facing a credibility gap within the COP system, within this model of insider policymaking, and it’s only going to get worse until real changes and instrumental policies are enacted.”

Part of the solution, he adds, is to include more sociologists and political scientists at COP, because “the problems we face around climate change are not primarily scientific anymore.”

During the summit, UML joined the Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) coalition, which is part of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change.

“The core idea is that the right to information about climate change, and the right to participate in decision-making and climate action, is a universal human right,” says Rooney-Varga, who hopes students will be part of the UML delegation at COP27 in Egypt.

William Lefebvre, a first-year environmental science major who attended the CCI’s COP26 recap discussion at Alumni Hall, says he’s interested in applying.

“I think as a nation, we need to come together and see this as an issue. People can’t be afraid of the science,” says Lefebvre, who is from Leominster, Massachusetts. “I’m blown away by how integrated UMass Lowell is with global topics, especially with environmental science.”